The Portreath Branch

followed by the

The PoldiceTramway

Credits, Many thanks to all contributors - please see a list on the home page.

Members and general visitors to the CRS site will be interested in visiting http://www.railmaponline.com From the opening page a full map of the UK can be accessed which can then be enlarged to show every railway line in the UK. Not just today's network but lines from the past have been overlaid. As you zoom in sidings and even tramways become visible.

A valuable tip from Guy Vincent.

A valuable tip from Guy Vincent.

N.B Click on picture to obtain an enlargement and further details

PORTREATH - the Branch and incline Roy Hart

The incline at Portreath was opened, with the rest of the branch, in 1837. It was powered by a cornish beam engine at the summit of the incline, which was known as the 'Lady Basset'. One wagon up and one down. This engine was replaced, towards the end of the 19th contury, by a smaller, rotary engine which lasted until the end.

Photos of the engine building show that it resembled a conventional Cornish engine house -and this is why.

The branch fell into disuse by 1930, but the GWR kept the engine in good order. The branch closed beyond North Pool siding in 1936 and all remained in situ until the invasion scare of 1940, when the track on the incline was swiftly removed and a concrete barrier (still there today) was erected at the base of the incline, presumably to prevent the Nazi hordes from invading Illogan.

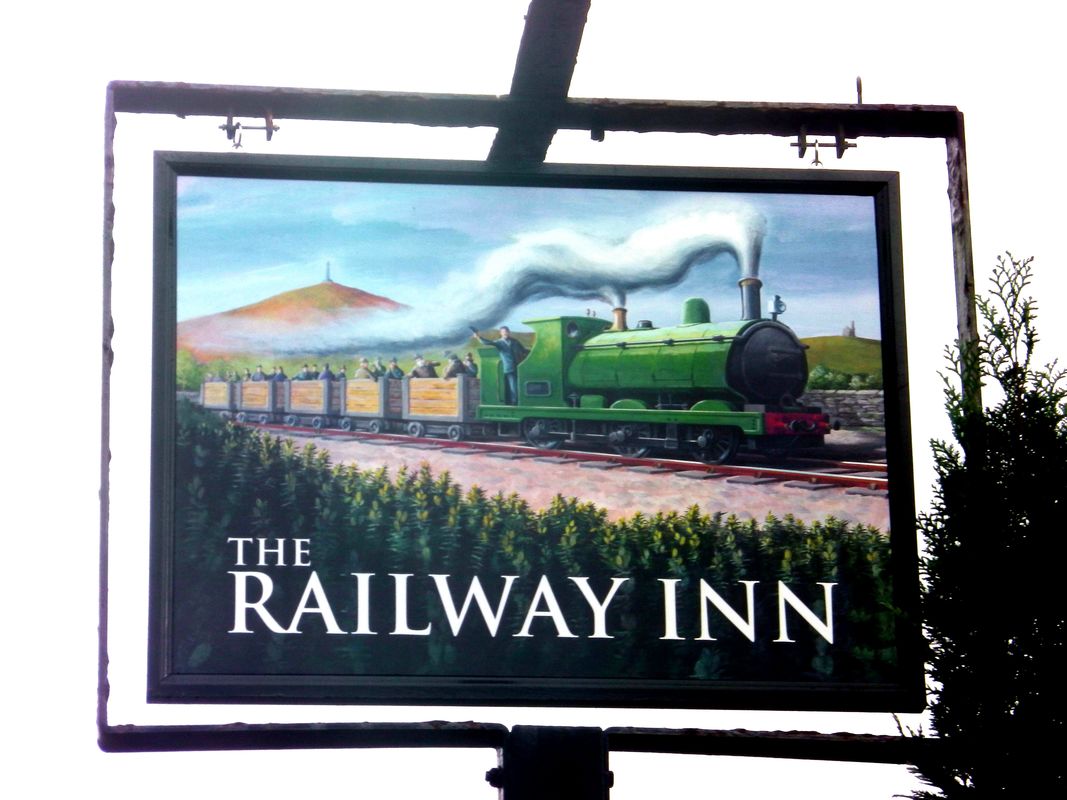

The rest of the branch was lifted in the early months of 1945. Interestingly, the locomotive which hauled the demolition trains was pannier tank 1799, immortalised for many years on the pub sign at the Railway Inn at Illogan Highway. This engine was shedded for many years at Carn Brea and spent most of its life in West Cornwall.

The incline at Portreath was opened, with the rest of the branch, in 1837. It was powered by a cornish beam engine at the summit of the incline, which was known as the 'Lady Basset'. One wagon up and one down. This engine was replaced, towards the end of the 19th contury, by a smaller, rotary engine which lasted until the end.

Photos of the engine building show that it resembled a conventional Cornish engine house -and this is why.

The branch fell into disuse by 1930, but the GWR kept the engine in good order. The branch closed beyond North Pool siding in 1936 and all remained in situ until the invasion scare of 1940, when the track on the incline was swiftly removed and a concrete barrier (still there today) was erected at the base of the incline, presumably to prevent the Nazi hordes from invading Illogan.

The rest of the branch was lifted in the early months of 1945. Interestingly, the locomotive which hauled the demolition trains was pannier tank 1799, immortalised for many years on the pub sign at the Railway Inn at Illogan Highway. This engine was shedded for many years at Carn Brea and spent most of its life in West Cornwall.

The 'Railway Inn' public house at Illogan Highway fell on bad times a few years ago but has since reopened with a new sign as seen below. We wish the Landlord every success with the new venture.

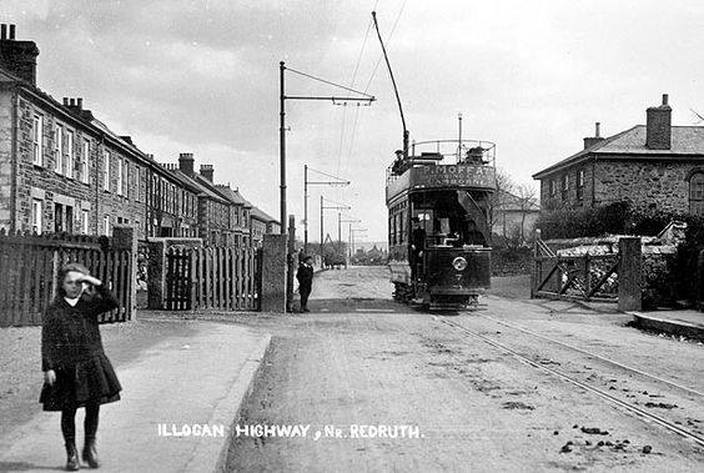

The new Railway Inn' sign at Illogan Highway Level Crossing. 18th November 2017 Copyright Keith Jenkin It is a pity that the new sign did not show the level crossing over the road and street tramway. It could have included one of the colourful tramcars which once served the Camborne - Redruth tramway waiting by the gates. The sign is also inaccurate in that the Portreath branch never carried passengers.

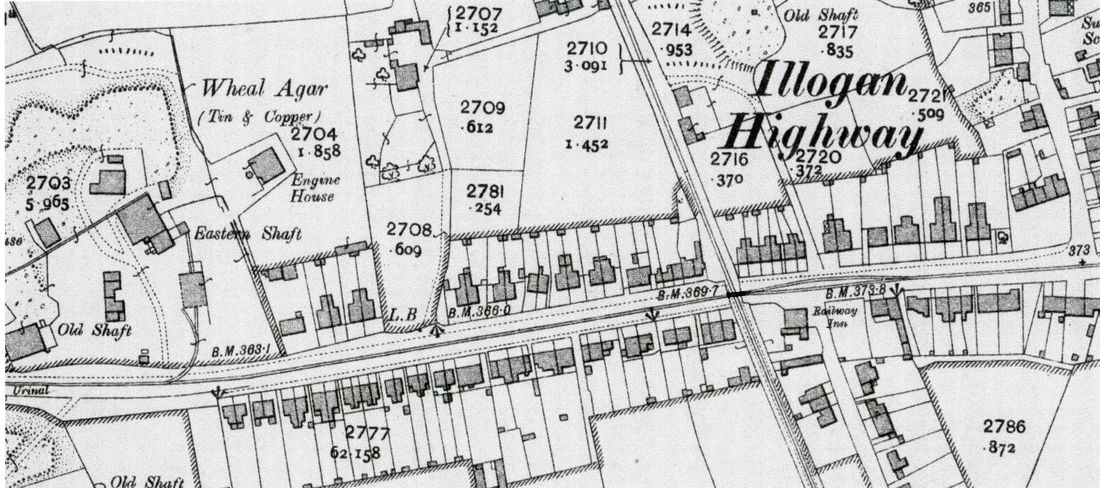

Illogan Highway Level Crossing from the 1908 25 inch OS with Permission of National Library of Scotland. The Portreath branch line starts from nearby Portreath Junction, to the bottom of the map and continues towards Portreath Harbour at the top of the map. The 4 foot gauge tramway ran from Redruth, to the right to Camborne, to the left. Mineral trams ran from Wheal Agar mine to Tovaddon mine.

The map accompanying the feature on the pub sign at Illogan Highway shows some interesting features. Among them is Wheal Agar and its connection to the Camborne-Redruth tram system.

At the time of the map (1908) Wheal Agar was on its last legs; it had seldom made much profit and before World War 1 it was amalgamated with East Pool mine. East Pool, in turn, suffered a catastrophic underground collapse in 1918 and had to suspend operations. They set to work on a new shaft (known as Taylors, after the mine captain) on a new site, near Wheal Agar , (whose engines survived, derelict until 1946). Taylor,s had no processing facilities, so they took over Agar's rights to use the tramway along the streets to the processing plant at Tolvaddon. Thus, although the streets of Pool no longer saw trams after 1927, there was the daily hazard of the mineral tram through the silent streets, accompanied by yells of 'tincar'.

The tram tracks were gradually removed (apart from this section) but the tincar ran until 1935. East Pool and Agar Limited cast the acronym EPAL on their ingots (and in white brick, as everybody knows who passes the site today). In 1935 East Pool opened an aerial ropeway across country to Tolvaddon, which carried their ore until the mine closed in 1945. Taylors engine worked on to keep South Crofty dry, until 1954.

The poles which carried the tramwires survived until the mid-1960s as lamp posts between Camborne and Redruth.

Roy Hart Many thanks Roy

At the time of the map (1908) Wheal Agar was on its last legs; it had seldom made much profit and before World War 1 it was amalgamated with East Pool mine. East Pool, in turn, suffered a catastrophic underground collapse in 1918 and had to suspend operations. They set to work on a new shaft (known as Taylors, after the mine captain) on a new site, near Wheal Agar , (whose engines survived, derelict until 1946). Taylor,s had no processing facilities, so they took over Agar's rights to use the tramway along the streets to the processing plant at Tolvaddon. Thus, although the streets of Pool no longer saw trams after 1927, there was the daily hazard of the mineral tram through the silent streets, accompanied by yells of 'tincar'.

The tram tracks were gradually removed (apart from this section) but the tincar ran until 1935. East Pool and Agar Limited cast the acronym EPAL on their ingots (and in white brick, as everybody knows who passes the site today). In 1935 East Pool opened an aerial ropeway across country to Tolvaddon, which carried their ore until the mine closed in 1945. Taylors engine worked on to keep South Crofty dry, until 1954.

The poles which carried the tramwires survived until the mid-1960s as lamp posts between Camborne and Redruth.

Roy Hart Many thanks Roy

Tram number 7 stands just beyond the tracks of the Portreath branch. In this posed picture you will that the tram which is heading for Redruth is about to enter a tramway passing loop on the far side of the railway crossing - this was the third passing point out from Redruth for the trams. The tramways passenger service ceased in 1927 although this crossing continued in railway use until 1936 as a sub of the Portreath line remained to serve North Pool siding which was north of here. There were other crossings where the standard gauge metals were crossed by the tramway - these were at the top of East Hill - the North Crofty branch and at Wesley Street Camborne where the Roskear branch crossed on its way towards Holmans Boiler Works. Picture from the Alan Harris Collection.

This marvellous picture of what might have been the first railtour in Cornwall, almost certainly on the Portreath branch. This is long before the days of 'Petticoat Government' so it must have been a pleasure outing along the branch. Take a look at the passengers dressed in all their finery. There appear to be nine ladies three young men and two children. The driver poses on his steed. From the steps leaning against the wagon which is fitted with 'dumb buffers', this is obviously a posed photograph, and what a gem. Perhaps the party were just about to disembark for a walk to the beach or had just returned from an outing there. The date on the postcard is 4th August 1904.

A much appreciated comment from Roy Hart who had an early view of this photograph.

This photo was taken at the approach to the summit of Portreath incline. I think 'Directors' is someone's guess, or a joke, as the occupants of the wagon are mostly female. I'd say directors of any company at that time were exclusively male!). There appears to be only one male present over the age of about 15. This is some sort of social gathering (note the ladder up to the wagon) and is perhaps the GWR doing a favour for the Bassets, who owned all the land around there.

The incline summit is in the distance around the curve. The winding engine is off the picture to the left.

I would date this around 1900. Note that the wagon has 'dumb' buffers. The engine is an early 0-6-0 saddle tank from Carn Brea shed.

The Portreath branch was most certainly not authorised for passenger trains (though there were excursions in Hayle Railway/ WCR days, when rules were lax) so for this to happen in the GWR era, you needed big influence!

Roy Many thanks Roy

This photo was taken at the approach to the summit of Portreath incline. I think 'Directors' is someone's guess, or a joke, as the occupants of the wagon are mostly female. I'd say directors of any company at that time were exclusively male!). There appears to be only one male present over the age of about 15. This is some sort of social gathering (note the ladder up to the wagon) and is perhaps the GWR doing a favour for the Bassets, who owned all the land around there.

The incline summit is in the distance around the curve. The winding engine is off the picture to the left.

I would date this around 1900. Note that the wagon has 'dumb' buffers. The engine is an early 0-6-0 saddle tank from Carn Brea shed.

The Portreath branch was most certainly not authorised for passenger trains (though there were excursions in Hayle Railway/ WCR days, when rules were lax) so for this to happen in the GWR era, you needed big influence!

Roy Many thanks Roy

Hugh Davies Portreath 1954 4173 'Photos from the Fifties collection' [email protected] From the Alan Harris collection

Portreath 1954 4172 'Photos from the Fifties collection' [email protected] From the Alan Harris collection. N.B. The coal in this picture certainly wouldn't have come down the branch - it had closed long before. It must therefore have been unloaded from a ship by the crane. The trackwork shows some very tight curves, note the use of sub points. One can clearly be seen to the left of this picture.

A WALK ALONG THE TRACK BED OF THE PORTREATH BRANCH IN THE SUMMER OF 1964

A fascinating story of life in St Ives in the '50's and the exploration of remains of the Portreath branch

An article by Laurence Hansford.

A fascinating story of life in St Ives in the '50's and the exploration of remains of the Portreath branch

An article by Laurence Hansford.

Portreath had always fascinated me.

Back in the 1950s very few people had the money to keep a car; those in St Ives were mostly in the hands of Doctors, Solicitors, Shopkeepers, owners of the larger Hotels and the like. Certainly, my parents never owned one. Bicycles were not much used either because of the hilly nature of the terrain. Consequently most people moved around either by train or bus and if this meant changing several times some relatively local places were rarely visited.

I became aware of Portreath and its little harbour thanks to a Sunday School outing in about 1954. These were hugely popular and eagerly anticipated as most kids rarely went anywhere (other than to school). Places like Camborne and Redruth were big enough that they could hire a complete train to take their Sunday Schools to St Ives for the day to enjoy the beaches and a picnic. At St Ives, instead, the various denominations usually hired one or more coaches from either Crimson Tours or Stevens Tours (both based in St Ives with fleets of Bedford OB petrol coaches). The Parish Church was no exception and theirs would typically run along the coast road to Lands End, stopping at Sennen Cove for a picnic.

On this occasion, instead, we went in the other direction, taking in Upton Towans, Gwithian, the Red River (very red then), Godrevy, stopping at Hells Mouth to peer over the edge (completely unfenced). Portreath was next stop where most of the participants either headed for the small beach or went to find a sweet shop to buy liquorice, sherbet or gob-stoppers. I was immediately taken by the compact little port, still very active with many huge piles of coal and small coasters being unloaded by ancient cranes. Unfortunately, I seem to remember it was all closed off preventing me from wandering about the quay-sides.

Then I saw what appeared to be an enormous groove cut right through the cliff from top to bottom, pointing straight into the harbour. It was obviously man-made as its inside floor was straight, flat and of uniform width, wide enough for a couple of lorries. It appeared to be abandoned as the only feature was a wall across near the bottom, blocking it off. The absence of virtually any vegetation suggested that it hadn’t been out of use for that long but what had it been used for?

I had seen pictures of funicular railways in books so put two & two together and guessed that one had been here in the days before the motor lorry although where it went, what was at the other end and what the cargo was remained a mystery. I decided I had to find out but it was easier said than done.

Nobody I knew had the faintest idea and it is very easy to forget that very few of the railway books we take for granted had been published by the early 1950s. A visit to even a large branch of W H Smiths was only likely to yield I Spy Railways, the Observers Book Of Railway Locos or the various Ian Allen booklets. This I found very frustrating as I could clearly see Godrevey Lighthouse from any window at the front of the house and knew that Portreath was just round the corner.

Then, one day a couple of years later, one of our Guests (my parents kept a Guest House) left behind a tattered old Ordnance Survey 1 inch Tourist Map printed in 1922 which was falling apart. But, lo and behold, it showed Portreath and there it was, a thin spidery black trace leading to the main railway line at Carn Brea. Equally important, it had the magic initials G.W.R. printed above it. If confirmation was need, the key in the bottom left corner said “Mineral Lines and Tramways”. I still have the map.

With this new information I started to ask everyone down at the station if they knew anything about it. Well, they did, but not a lot. I managed to establish that it was a single line branch worked by tank-engines as far as the top of the incline, where a stationery steam engine let the trucks up and down on a pair of tracks. The engines never went beyond this. It had gone out of use sometime before the war and the track lifted.

I had hoped to find someone who had actually worked the line but without success. This initially surprised me as there were plenty of people around who started work well before 1922 but I soon discovered the reason.

If you wanted to progress in your railway career, when the time came for promotion you would be offered the next available vacancy; you might be lucky and get a choice of 2 or 3 but they would be very unlikely to be on your doorstep. To get from engine cleaner to top-link driver could involve many moves. Of course, you could always turn down the Company’s kind offers but this was frowned on as it tended to suggest that you were lacking in ambition and drive. I found that the end result of this was that all the engine crews originated from anywhere on the system - apart from West Cornwall.

Maybe if I had been able to ask around in the Camborne/Redruth area I might have had more luck but the opportunity never arose. Before I left Cornwall I did manage another couple of trips through Portreath but these were not particularly helpful in my quest for information.

Then one day in early 1964 I was in a large bookshop in Reading (long gone) and spotted C R Clinker’s THE RAILWAYS OF CORNWALL 1809-1963 for 10 shilling and 6 pence which had just been published. I bought it there and then. This little gem told me that the line to Portreath had been opened by the Hayle Railway in 1837 and closed by the GWR on the 1st January 1936 although the track was left in place. However the track was removed from the incline (only) in August 1940, presumably so as not to make life too easy if the Germans decided to land at Portreath. The rest was left in situ until as late as October 1945, a mere 19 years previously. This made me think that the track-bed might still be passable and that there might even be some bits and bobs left lying around. I decided to investigate next time I visited Cornwall.

This happened in the second half of August 1964 so one day when the weather looked promising I bought a railway ticket from St Ives to Redruth where I jumped on the next bus running back to Camborne along the main road, the old A30. I took my tattered old map with me so as try to identify where the track had crossed the road. My map reading must have been quite good because at that point was a pub which I think was just called The Railway. Having noted the spot, I stayed on the bus until I got to the East Pool Winding Engine because I had been past it a number of times but had never had the opportunity to have a good look. In those days you could walk right up to it and it looked very forlorn and forgotten. My recollection is that it gave the impression that the scrap-men had been but didn’t think it was worth the effort to pull it to pieces. Very sad.

Having tried (and failed) to work out where its mine shaft was, I walked across the road and found a small Bakers Shop, attracted by the aroma of Pasties which had just come out of the oven. The smell was so good I bought two. I meant to keep one back for later but they were so delicious that I ate them both as I walked back to look for traces of the Portreath line. Could the Bakers still be there after all these years, I wonder?

Back at the pub, there were certainly no remains of track in the road or even clues to where it had been: The tarmac was just smooth and uniform. However there was a likely looking gap, just the right width for a railway line, between the houses on the North side of the road and, on the South side was another gap just to the Right of the pub. As I could see no other suitable crossing places I came to the conclusion that this had to be the right spot. Along the Eastern side of the pub ran a lane (which I see is now called Druids Road) heading in the direction of Carn Brea which, according to my map, crossed the main railway line on an over-bridge so I walked up it to see what could be seen.

Once I got past the few houses, the vista opened out into what I can only describe as scrubland with signs of much earlier activity. It was about here I found what I was looking for: On the right was a railway cutting which curved away from me to the Left and it contained some old trucks! Anyway, I carried on up to the railway bridge, from where I got an excellent view of the main line in both directions and, if I looked towards Camborne I could see where the curved cutting joined it and, beyond it, Carn Brea Yard.

Walking back down the lane, I found a weak part of the fence and, as there was nobody about, scrambled down into the cutting where I found that there were two sidings, one much shorter than the other, which between them contained something like twenty or thirty assorted trucks. They gave the impression that they were being stored for when a need arose, rather than having been dumped.

I didn’t venture too far towards Carn Brea Yard (for fear of being spotted) but in the other direction I could see that the longer siding extended all the way round the curve, in effect through virtually 90°, and then carried on straight, heading in the direction of the gap at the side of the pub. Beyond the buffer stops the cutting ended abruptly. This was obviously all that was left of the Branch. The shorter siding, instead, was restricted to the curved section of the cutting, on the outside of the curve.

I got very excited when I noticed that at the far end of each siding, the last section of track consisted of much lighter section rail held in much light chairs which were keyed on the inside of the track. This I had never seen before. I looked to see if there was any lettering on the chairs but they were so rusty that any traces had disappeared. I wonder if these were of Hayle Railway, West Cornwall Railway or just plain Cornwall Railway origin?

Anyway, I took some photos and retreated up the embankment to the lane, which I followed back to the main road, which I crossed. Here was another lane between the houses, heading North in the direction of Portreath; how very convenient. Once again I didn’t have to go very far until I got to practically open moorland. In fact, behind the houses facing the A30 and their gardens there were very few buildings (although there were plenty of traces of earlier activity) so it was easy to find were the track had been.

The terrain here was practically flat and level and the track-bed could easily have been confused for a farm track as it went for a considerable distance between a pair of low dry-stone walls and was actually being used as a track so was easy to walk along. What identified it as an old railway line was that its floor was level, in places running on a shallow embankment whilst in other places a foot or two below ground level and there were a number of dilapidated gates on both sides where presumably there had been occupational crossings.

Once I got to the end of the stretch still used as a track, things got more difficult. The usual impenetrable Cornish mix of brambles, gorse, nettles and bracken had taken hold, taking advantage of the shelter afforded by the stone walls, forcing me to walk alongside where I could without blatantly trespassing. By this time the moorland had given way to a field system (mostly grass) so it wasn’t too difficult but there were parts where I had to resort to the public right-of-way. By this time the track bed was pretty much all on a modest embankment and my recollection is that it was never more than about 15 feet high.

Then I found my first bridge on the line; the nicely constructed masonry bridge over Spar Lane, a made-up public highway. I took a photo of this, noting how small it was and the fact that the road-way had been excavated to give even modest headroom, barely enough for even a small lorry. I see that in the meantime this bridge has been cleared away and the road straightened.

Not much further along, I came across another even smaller bridge, this time just about large enough for a man to drive a cow. Of very similar style and construction to the Spar Lane bridge (except that this one was at right angles to the line), the odd thing was that it had been blocked off in the distant past with what looked like an old bedstead and other bits of sundry old iron. Brambles had finished the job off making the whole utterly impenetrable. However, it didn’t stop me from taking a photo.

The next bridge I found had, unfortunately, already been mostly demolished. I am not sure now where exactly it was but it was somewhere in the vicinity of the other two because most of the line was not high enough off the ground to make an underbridge necessary or even possible. I knew that this was the site of a bridge because although one abutment and embankment had been completely flattened the other one was still intact and you can see it in another of the photos. I think it was the access to a farm and no doubt it had to go to let modern farm vehicles through. It was near here that I spotted one of two railway relics – 3 short pieces of Barlow rail (a bit like Brunel bridge rail but laid directly in the ballast)– sitting on top of a wall. Apparently the Hayle Railway was originally laid with short cast iron rails on stone blocks but it seems that when the West Cornwall took over, the main line was laid with Barlow rails direct on the ballast. Whether it was ever used on the branch I couldn’t say; does anyone else know? Some sources say that when it was adopted in South Wales it was soon found to be unstable and liable to gauge-spread, especially on bends. Consequently, miles of it were available very cheap and it was used for all sorts of things, apart from railway track!

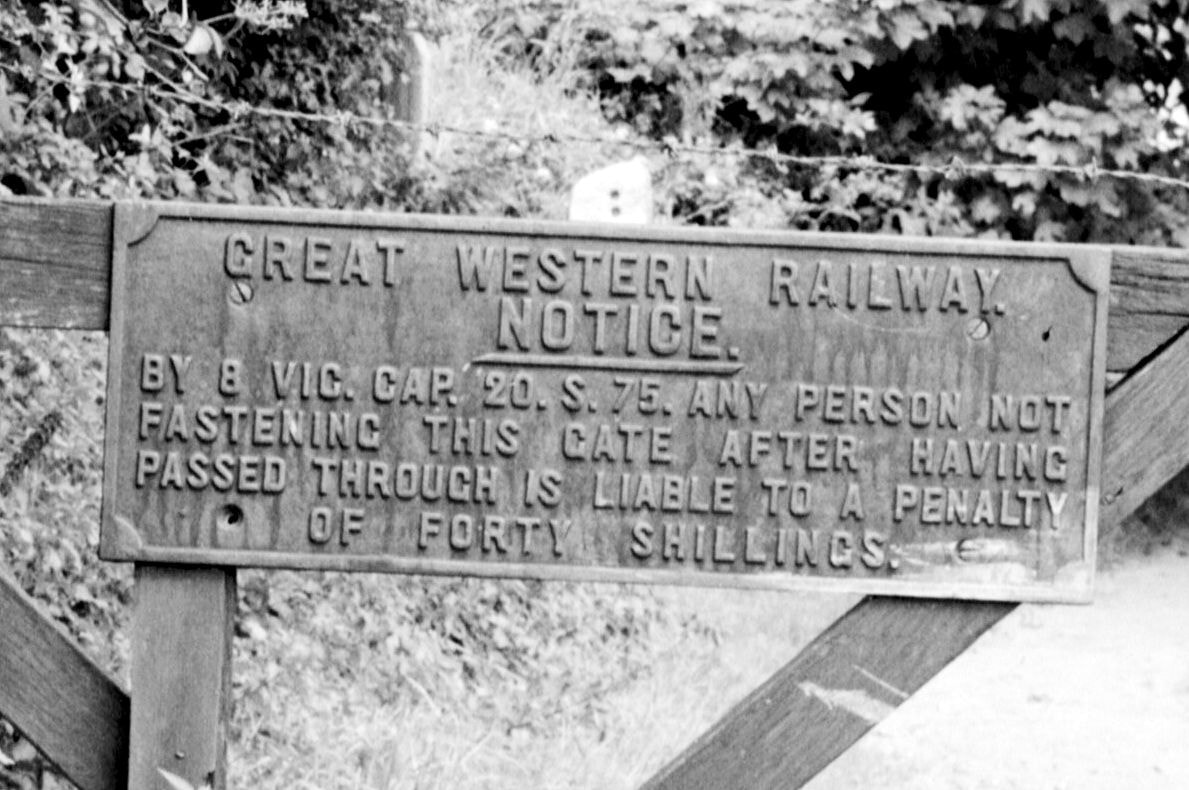

There then followed about half a mile of straightish track bed laid out more or less at ground level before going into a gentle curve to the left, much of which was in a shallow cutting. The other relic – a GWR “shut the gate” notice - was in the same area and probably was from the branch, although not in its original position as it had been screwed on the inside of the gate. In fact, along the line there were a number of locations where farm tracks crossed and the wooden gates had been left in situ but I particularly noted that, apart from here, all other cast iron notices had gone.

This shallow cutting then opened out and took a rather sharp curve to the right before ending abruptly at the top of a chasm with a flat and straight bottom cut into the cliff, leading directly into the harbour. Surprisingly, not much vegetation had been allowed to take hold down the sides of the incline; I think this was because it was clearly still in use as a track. As a result, the view looking down it was almost breath-taking.

Still at the top looking backwards, vegetation was a different matter –much of the shallow cutting would have been impassable without a machete and I had had to find a way round it. I did try to locate where the winding engine house had been but the plant life made it very difficult, as did various little hillocks scattered around. Had the greenery been cleared away, I rather suspect that it would have revealed that the area had been used as a dumping ground for builders’ rubble. All I could do was speculate as to what had been where.

I took a couple of photos but the incline and the harbour beyond were too inviting so off I went down the track, taking a few more photos as I went. Near the bottom, the cutting changes into an embankment under which a bridge gives access to houses, which I believe is still in existence. Almost above it, the wall built across the track bed was still there but this proved no barrier to a reasonably fit and agile Cornish lad! In passing I noticed that someone had scrawled the word PRIVATE on the other side of the wall, presumably implying that I had been on private property but in those days I’m afraid I didn’t worry about such things.

Whilst walking down the incline I had been treated to a wonderful view of the harbour but I was disappointed to see that there were no coasters tied-up at any of the quays. Although there was no visible activity, the port was clearly still in use as there were many large heaps of different types of coal dotted about. (It must be remembered that in 1964 domestic central heating was virtually unknown and coal & coke were used for all manner of heating as well as other purposes, having a near monopoly.)

As I got closer, from my elevated position, I could see that as well as no activity there seemed to be no people about either but the gates were wide open. In fact, because it was still considered an industrial village, it was off the tourist’s beaten track and the air of desertion extended from the port to the whole of Portreath. About the only place a few visitors could be spotted was scattered about on the beach.

When I got down to ground level there was still nobody about so in I went, hoping to find some remnants of railway track. As nobody challenged me I was able to have a really good nose round but I have to report that I was thoroughly disappointed. Virtually the whole area not covered by heaps of coal was covered by well ground-in coal dust (in the same way as much of the wharfage at Hayle, except that there the rails in use were visible) and it was impossible to tell if any track was lurking below. I did think I had found where track had once been along the South-Western edge of the outer dock but, looking at the 25 inch O.S. map of the Library of Scotland, this is shown as detached from the rest of the system and I suspect was for one of the travelling steam cranes once in use.

Having not even found a sniff of anything else to show that a railway had been there, I left the port area and had a wander around until I saw a Western National single-decker come into view which I then caught back to… Redruth or was it Camborne? I can’t now remember, not that it matters as either would have got me back to St Ives at the end of an interesting, if a bit disappointing, day.

Thinking about it later I have often wondered why the Hayle Railway, obviously conceived to serve the Port of Hayle, built a branch (at considerable expense if one considers the incline and associated engine) to the Port of Portreath, their only local competitor. This is especially odd when Harvey & Co and the Cornish Copper Co, who between them controlled Hayle, were both closely concerned in its promotion. My own view (and it is just that) is that it was a blocking move to pre-empt some other railway company from getting there first either by buying up the Poldice Tramroad and bringing it up-to-date or building a new line from scratch. There may also have been the thought that it would give them a measure of control over Portreath’s traffic.

In reality Portreath could never have challenged Hayle’s supremacy as its very restricted site meant it could only ever accommodate coastal vessels of the smallest size. Moreover, it did not have the benefit of the sheltering effect of St Ives Bay, its entrance being wide open to northerly gales. This was demonstrated to me quite dramatically on another occasion.

I had a much older sister who moved “up country” and got married when I was still a small child. In the second half of the ‘50s she and her husband became the proud owners of a Ford Prefect and they would come down and stay with us periodically with the object of sunning themselves on the beach. On a very blustery but dry day, totally unsuited to the beach, during one such visit in the late spring of 1959 (if my memory is correct) it was decided that the best option was to go for a drive in the car. But where to? As they had done West Penwith pretty comprehensively I suggested a run up the North Coast, taking the same route as my Sunday School outing of years before.

Of course, when we got to Portreath I persuaded them that we should park and take a look around. Just by chance it was high tide and a small group of spectators had gathered to watch a loaded coaster approaching the port. The wind hadn’t abated and was blowing in gusts making the sea very choppy, tossing the ship around like a cork. Nonetheless it kept going and as it got to the harbour mouth we could see that the helmsman was having a heck of a job to stop the ship from running into the rocks on the North side of the entrance. I can still hear the thud-thud-thud-thud of the oil engine working flat out and one could practically feel the sense of relief once it made it to the calmer waters of the harbour basin. It must have been a heart-in-mouth operation for the crew and I hate to think what would have happened if the engine had failed. Imagine trying to do that with a sailing ship a century earlier!

Back in the 1950s very few people had the money to keep a car; those in St Ives were mostly in the hands of Doctors, Solicitors, Shopkeepers, owners of the larger Hotels and the like. Certainly, my parents never owned one. Bicycles were not much used either because of the hilly nature of the terrain. Consequently most people moved around either by train or bus and if this meant changing several times some relatively local places were rarely visited.

I became aware of Portreath and its little harbour thanks to a Sunday School outing in about 1954. These were hugely popular and eagerly anticipated as most kids rarely went anywhere (other than to school). Places like Camborne and Redruth were big enough that they could hire a complete train to take their Sunday Schools to St Ives for the day to enjoy the beaches and a picnic. At St Ives, instead, the various denominations usually hired one or more coaches from either Crimson Tours or Stevens Tours (both based in St Ives with fleets of Bedford OB petrol coaches). The Parish Church was no exception and theirs would typically run along the coast road to Lands End, stopping at Sennen Cove for a picnic.

On this occasion, instead, we went in the other direction, taking in Upton Towans, Gwithian, the Red River (very red then), Godrevy, stopping at Hells Mouth to peer over the edge (completely unfenced). Portreath was next stop where most of the participants either headed for the small beach or went to find a sweet shop to buy liquorice, sherbet or gob-stoppers. I was immediately taken by the compact little port, still very active with many huge piles of coal and small coasters being unloaded by ancient cranes. Unfortunately, I seem to remember it was all closed off preventing me from wandering about the quay-sides.

Then I saw what appeared to be an enormous groove cut right through the cliff from top to bottom, pointing straight into the harbour. It was obviously man-made as its inside floor was straight, flat and of uniform width, wide enough for a couple of lorries. It appeared to be abandoned as the only feature was a wall across near the bottom, blocking it off. The absence of virtually any vegetation suggested that it hadn’t been out of use for that long but what had it been used for?

I had seen pictures of funicular railways in books so put two & two together and guessed that one had been here in the days before the motor lorry although where it went, what was at the other end and what the cargo was remained a mystery. I decided I had to find out but it was easier said than done.

Nobody I knew had the faintest idea and it is very easy to forget that very few of the railway books we take for granted had been published by the early 1950s. A visit to even a large branch of W H Smiths was only likely to yield I Spy Railways, the Observers Book Of Railway Locos or the various Ian Allen booklets. This I found very frustrating as I could clearly see Godrevey Lighthouse from any window at the front of the house and knew that Portreath was just round the corner.

Then, one day a couple of years later, one of our Guests (my parents kept a Guest House) left behind a tattered old Ordnance Survey 1 inch Tourist Map printed in 1922 which was falling apart. But, lo and behold, it showed Portreath and there it was, a thin spidery black trace leading to the main railway line at Carn Brea. Equally important, it had the magic initials G.W.R. printed above it. If confirmation was need, the key in the bottom left corner said “Mineral Lines and Tramways”. I still have the map.

With this new information I started to ask everyone down at the station if they knew anything about it. Well, they did, but not a lot. I managed to establish that it was a single line branch worked by tank-engines as far as the top of the incline, where a stationery steam engine let the trucks up and down on a pair of tracks. The engines never went beyond this. It had gone out of use sometime before the war and the track lifted.

I had hoped to find someone who had actually worked the line but without success. This initially surprised me as there were plenty of people around who started work well before 1922 but I soon discovered the reason.

If you wanted to progress in your railway career, when the time came for promotion you would be offered the next available vacancy; you might be lucky and get a choice of 2 or 3 but they would be very unlikely to be on your doorstep. To get from engine cleaner to top-link driver could involve many moves. Of course, you could always turn down the Company’s kind offers but this was frowned on as it tended to suggest that you were lacking in ambition and drive. I found that the end result of this was that all the engine crews originated from anywhere on the system - apart from West Cornwall.

Maybe if I had been able to ask around in the Camborne/Redruth area I might have had more luck but the opportunity never arose. Before I left Cornwall I did manage another couple of trips through Portreath but these were not particularly helpful in my quest for information.

Then one day in early 1964 I was in a large bookshop in Reading (long gone) and spotted C R Clinker’s THE RAILWAYS OF CORNWALL 1809-1963 for 10 shilling and 6 pence which had just been published. I bought it there and then. This little gem told me that the line to Portreath had been opened by the Hayle Railway in 1837 and closed by the GWR on the 1st January 1936 although the track was left in place. However the track was removed from the incline (only) in August 1940, presumably so as not to make life too easy if the Germans decided to land at Portreath. The rest was left in situ until as late as October 1945, a mere 19 years previously. This made me think that the track-bed might still be passable and that there might even be some bits and bobs left lying around. I decided to investigate next time I visited Cornwall.

This happened in the second half of August 1964 so one day when the weather looked promising I bought a railway ticket from St Ives to Redruth where I jumped on the next bus running back to Camborne along the main road, the old A30. I took my tattered old map with me so as try to identify where the track had crossed the road. My map reading must have been quite good because at that point was a pub which I think was just called The Railway. Having noted the spot, I stayed on the bus until I got to the East Pool Winding Engine because I had been past it a number of times but had never had the opportunity to have a good look. In those days you could walk right up to it and it looked very forlorn and forgotten. My recollection is that it gave the impression that the scrap-men had been but didn’t think it was worth the effort to pull it to pieces. Very sad.

Having tried (and failed) to work out where its mine shaft was, I walked across the road and found a small Bakers Shop, attracted by the aroma of Pasties which had just come out of the oven. The smell was so good I bought two. I meant to keep one back for later but they were so delicious that I ate them both as I walked back to look for traces of the Portreath line. Could the Bakers still be there after all these years, I wonder?

Back at the pub, there were certainly no remains of track in the road or even clues to where it had been: The tarmac was just smooth and uniform. However there was a likely looking gap, just the right width for a railway line, between the houses on the North side of the road and, on the South side was another gap just to the Right of the pub. As I could see no other suitable crossing places I came to the conclusion that this had to be the right spot. Along the Eastern side of the pub ran a lane (which I see is now called Druids Road) heading in the direction of Carn Brea which, according to my map, crossed the main railway line on an over-bridge so I walked up it to see what could be seen.

Once I got past the few houses, the vista opened out into what I can only describe as scrubland with signs of much earlier activity. It was about here I found what I was looking for: On the right was a railway cutting which curved away from me to the Left and it contained some old trucks! Anyway, I carried on up to the railway bridge, from where I got an excellent view of the main line in both directions and, if I looked towards Camborne I could see where the curved cutting joined it and, beyond it, Carn Brea Yard.

Walking back down the lane, I found a weak part of the fence and, as there was nobody about, scrambled down into the cutting where I found that there were two sidings, one much shorter than the other, which between them contained something like twenty or thirty assorted trucks. They gave the impression that they were being stored for when a need arose, rather than having been dumped.

I didn’t venture too far towards Carn Brea Yard (for fear of being spotted) but in the other direction I could see that the longer siding extended all the way round the curve, in effect through virtually 90°, and then carried on straight, heading in the direction of the gap at the side of the pub. Beyond the buffer stops the cutting ended abruptly. This was obviously all that was left of the Branch. The shorter siding, instead, was restricted to the curved section of the cutting, on the outside of the curve.

I got very excited when I noticed that at the far end of each siding, the last section of track consisted of much lighter section rail held in much light chairs which were keyed on the inside of the track. This I had never seen before. I looked to see if there was any lettering on the chairs but they were so rusty that any traces had disappeared. I wonder if these were of Hayle Railway, West Cornwall Railway or just plain Cornwall Railway origin?

Anyway, I took some photos and retreated up the embankment to the lane, which I followed back to the main road, which I crossed. Here was another lane between the houses, heading North in the direction of Portreath; how very convenient. Once again I didn’t have to go very far until I got to practically open moorland. In fact, behind the houses facing the A30 and their gardens there were very few buildings (although there were plenty of traces of earlier activity) so it was easy to find were the track had been.

The terrain here was practically flat and level and the track-bed could easily have been confused for a farm track as it went for a considerable distance between a pair of low dry-stone walls and was actually being used as a track so was easy to walk along. What identified it as an old railway line was that its floor was level, in places running on a shallow embankment whilst in other places a foot or two below ground level and there were a number of dilapidated gates on both sides where presumably there had been occupational crossings.

Once I got to the end of the stretch still used as a track, things got more difficult. The usual impenetrable Cornish mix of brambles, gorse, nettles and bracken had taken hold, taking advantage of the shelter afforded by the stone walls, forcing me to walk alongside where I could without blatantly trespassing. By this time the moorland had given way to a field system (mostly grass) so it wasn’t too difficult but there were parts where I had to resort to the public right-of-way. By this time the track bed was pretty much all on a modest embankment and my recollection is that it was never more than about 15 feet high.

Then I found my first bridge on the line; the nicely constructed masonry bridge over Spar Lane, a made-up public highway. I took a photo of this, noting how small it was and the fact that the road-way had been excavated to give even modest headroom, barely enough for even a small lorry. I see that in the meantime this bridge has been cleared away and the road straightened.

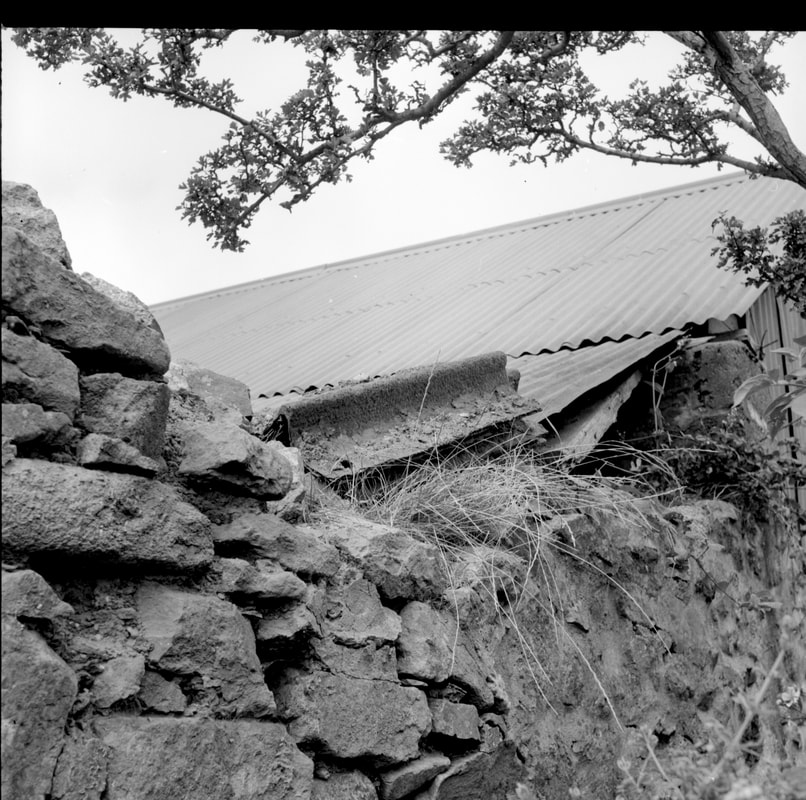

Not much further along, I came across another even smaller bridge, this time just about large enough for a man to drive a cow. Of very similar style and construction to the Spar Lane bridge (except that this one was at right angles to the line), the odd thing was that it had been blocked off in the distant past with what looked like an old bedstead and other bits of sundry old iron. Brambles had finished the job off making the whole utterly impenetrable. However, it didn’t stop me from taking a photo.

The next bridge I found had, unfortunately, already been mostly demolished. I am not sure now where exactly it was but it was somewhere in the vicinity of the other two because most of the line was not high enough off the ground to make an underbridge necessary or even possible. I knew that this was the site of a bridge because although one abutment and embankment had been completely flattened the other one was still intact and you can see it in another of the photos. I think it was the access to a farm and no doubt it had to go to let modern farm vehicles through. It was near here that I spotted one of two railway relics – 3 short pieces of Barlow rail (a bit like Brunel bridge rail but laid directly in the ballast)– sitting on top of a wall. Apparently the Hayle Railway was originally laid with short cast iron rails on stone blocks but it seems that when the West Cornwall took over, the main line was laid with Barlow rails direct on the ballast. Whether it was ever used on the branch I couldn’t say; does anyone else know? Some sources say that when it was adopted in South Wales it was soon found to be unstable and liable to gauge-spread, especially on bends. Consequently, miles of it were available very cheap and it was used for all sorts of things, apart from railway track!

There then followed about half a mile of straightish track bed laid out more or less at ground level before going into a gentle curve to the left, much of which was in a shallow cutting. The other relic – a GWR “shut the gate” notice - was in the same area and probably was from the branch, although not in its original position as it had been screwed on the inside of the gate. In fact, along the line there were a number of locations where farm tracks crossed and the wooden gates had been left in situ but I particularly noted that, apart from here, all other cast iron notices had gone.

This shallow cutting then opened out and took a rather sharp curve to the right before ending abruptly at the top of a chasm with a flat and straight bottom cut into the cliff, leading directly into the harbour. Surprisingly, not much vegetation had been allowed to take hold down the sides of the incline; I think this was because it was clearly still in use as a track. As a result, the view looking down it was almost breath-taking.

Still at the top looking backwards, vegetation was a different matter –much of the shallow cutting would have been impassable without a machete and I had had to find a way round it. I did try to locate where the winding engine house had been but the plant life made it very difficult, as did various little hillocks scattered around. Had the greenery been cleared away, I rather suspect that it would have revealed that the area had been used as a dumping ground for builders’ rubble. All I could do was speculate as to what had been where.

I took a couple of photos but the incline and the harbour beyond were too inviting so off I went down the track, taking a few more photos as I went. Near the bottom, the cutting changes into an embankment under which a bridge gives access to houses, which I believe is still in existence. Almost above it, the wall built across the track bed was still there but this proved no barrier to a reasonably fit and agile Cornish lad! In passing I noticed that someone had scrawled the word PRIVATE on the other side of the wall, presumably implying that I had been on private property but in those days I’m afraid I didn’t worry about such things.

Whilst walking down the incline I had been treated to a wonderful view of the harbour but I was disappointed to see that there were no coasters tied-up at any of the quays. Although there was no visible activity, the port was clearly still in use as there were many large heaps of different types of coal dotted about. (It must be remembered that in 1964 domestic central heating was virtually unknown and coal & coke were used for all manner of heating as well as other purposes, having a near monopoly.)

As I got closer, from my elevated position, I could see that as well as no activity there seemed to be no people about either but the gates were wide open. In fact, because it was still considered an industrial village, it was off the tourist’s beaten track and the air of desertion extended from the port to the whole of Portreath. About the only place a few visitors could be spotted was scattered about on the beach.

When I got down to ground level there was still nobody about so in I went, hoping to find some remnants of railway track. As nobody challenged me I was able to have a really good nose round but I have to report that I was thoroughly disappointed. Virtually the whole area not covered by heaps of coal was covered by well ground-in coal dust (in the same way as much of the wharfage at Hayle, except that there the rails in use were visible) and it was impossible to tell if any track was lurking below. I did think I had found where track had once been along the South-Western edge of the outer dock but, looking at the 25 inch O.S. map of the Library of Scotland, this is shown as detached from the rest of the system and I suspect was for one of the travelling steam cranes once in use.

Having not even found a sniff of anything else to show that a railway had been there, I left the port area and had a wander around until I saw a Western National single-decker come into view which I then caught back to… Redruth or was it Camborne? I can’t now remember, not that it matters as either would have got me back to St Ives at the end of an interesting, if a bit disappointing, day.

Thinking about it later I have often wondered why the Hayle Railway, obviously conceived to serve the Port of Hayle, built a branch (at considerable expense if one considers the incline and associated engine) to the Port of Portreath, their only local competitor. This is especially odd when Harvey & Co and the Cornish Copper Co, who between them controlled Hayle, were both closely concerned in its promotion. My own view (and it is just that) is that it was a blocking move to pre-empt some other railway company from getting there first either by buying up the Poldice Tramroad and bringing it up-to-date or building a new line from scratch. There may also have been the thought that it would give them a measure of control over Portreath’s traffic.

In reality Portreath could never have challenged Hayle’s supremacy as its very restricted site meant it could only ever accommodate coastal vessels of the smallest size. Moreover, it did not have the benefit of the sheltering effect of St Ives Bay, its entrance being wide open to northerly gales. This was demonstrated to me quite dramatically on another occasion.

I had a much older sister who moved “up country” and got married when I was still a small child. In the second half of the ‘50s she and her husband became the proud owners of a Ford Prefect and they would come down and stay with us periodically with the object of sunning themselves on the beach. On a very blustery but dry day, totally unsuited to the beach, during one such visit in the late spring of 1959 (if my memory is correct) it was decided that the best option was to go for a drive in the car. But where to? As they had done West Penwith pretty comprehensively I suggested a run up the North Coast, taking the same route as my Sunday School outing of years before.

Of course, when we got to Portreath I persuaded them that we should park and take a look around. Just by chance it was high tide and a small group of spectators had gathered to watch a loaded coaster approaching the port. The wind hadn’t abated and was blowing in gusts making the sea very choppy, tossing the ship around like a cork. Nonetheless it kept going and as it got to the harbour mouth we could see that the helmsman was having a heck of a job to stop the ship from running into the rocks on the North side of the entrance. I can still hear the thud-thud-thud-thud of the oil engine working flat out and one could practically feel the sense of relief once it made it to the calmer waters of the harbour basin. It must have been a heart-in-mouth operation for the crew and I hate to think what would have happened if the engine had failed. Imagine trying to do that with a sailing ship a century earlier!

1. The East Pool winding engine looking very forlorn. At the time of this photo it had been restored after weather damage (Note chimney brickwork) Copyright Laurence Hansford. The former East Pool Mine Yard, behind the engine house had recently been occupied by a company owned by two Scotsmen, who made their name when they succeeded in refloating the battleship Warspite when she was wrecked in Prussia Cove in 1947. They named their company (after their origin and their work) Macsalvors.

Cornish 'Whim' at Mitchell's shaft. East Pool Mine.

3. Moving west from the previous location and looking west from Druids the bridge which carries Druids Lane we look towards the old junction with the Portreath branch and Carn Brea Yard beyond. Note if you zoom in on the horizon you can see the headgear of both New Cookes Kitchen Shaft among the signal posts and Robinsons shaft next to the nearest telegraph pols.

5. The rusty old trucks are being stored on both the short siding in the foreground which was laid later and what was left of the branch running into the cutting nearly as far as the wall beyond. I am fairly certain that the house with two windows visible beyond the wall is actually the one on the other side of main road next on the right where the track went.

The branch was used from about 1960 to 67 for storing condemned stock. Copyright Laurence Hansford.

10. The now demolished arch over Spar Lane. Rather a patchwork, really; an elegant dressed granite arch surmounted by what amounts to neat dry-stone walling bedded in mortar to give it stability and capped by more dressed granite. This was very much in the style of the mine engine houses being built in Cornwall at the time which, I suppose, is hardly surprising. The upper part has been re-built at some time and capped with bricks to add a bit of colour. Copyright Laurence Hansford.

12. Continuing on its low embankment the line crossed this substantial arch which was choked with vegetation. This view from a lane serving Primrose Cottage - the lane is a public footpath. Another identical arch survives further south serving a little-used footpath connecting Broad Lane and Spar Lane. Copyright Laurence Hansford.

17. A the top of the incline at a widened out shallow cutting there were two lines and the house containing the engine for winding trucks up and down the incline. Laurence feels that he is looking towards the top of the incline. However as the area has been obliterated by housing one cannot be sure. Copyright Laurence Hansford.

21. The harbour seen from the top of the bridge over Glenfeadon Terrace. Lots of detail:- all the piles of different sorts of coal, the weigh-bridge hut with the side open, the cranes, the tall telegraph posts, the powere cables and the bell at the top of a post but no ships, hardly any people and definitely no railway track in sight. Notice how the motorists were much more disciplined in those days with practically all the parked cars facing the same way and none on the pavement!! Copyright Laurence Hansford.

23. I took this view along the south-western side of the quay-side, firmly of the opinion that I had found the only trace of where a railway line had once been. Only recently, on having studied the 25" map on the Library of Scotland website - it looks as though I as right but it also shows it detached from the rest of the system. Most likely it was for trundling a steam crane up and down. Have you spotted the two men leaning on the coal lorry having a chat. Copyright Laurence Hansford.

Many thanks to you for sharing your memories Laurence and for this fascinating article.

Taking a look at the top of the Portreath incine in November 2018.

A report by Peter Murnaghan

A report by Peter Murnaghan

I was in Portreath yesterday (26th November 2018) and decided to see if it was possible to explore the incline, as Google maps seemed to suggest that it could be done, at least, the uppermost threequarters. Sadly, that wasn't to be the case. At the very top. near where the winding house would have been, is a promising private road with a few bungalows, named The Incline. My picture shows how the road drops over the edge, just as the wagons would have done. However, you can only venture down less than a quarter of the way, before very stern Private notices prevent further access. One can get down about as far as an old underbridge, thought to have been a farm access between both sides of the incline.

The underbridge is now blocked off and the other, western side, is an impenetrable jungle of brambles surrounded by back garden fences.

I hope that my photos might be useful to include in the Gallery for the Portreath branch, as there aren't any recent views of the top of the incline. And the situation is greatly changed since Laurence Hansford's exploration in 1964.

I hope this is useful. Best wishes, Peter Murnaghan.

Many thanks Peter

The underbridge is now blocked off and the other, western side, is an impenetrable jungle of brambles surrounded by back garden fences.

I hope that my photos might be useful to include in the Gallery for the Portreath branch, as there aren't any recent views of the top of the incline. And the situation is greatly changed since Laurence Hansford's exploration in 1964.

I hope this is useful. Best wishes, Peter Murnaghan.

Many thanks Peter

Footnote - footsore. During WW2 my father was in the Home Guard based at Redruth. For exercise they had to run up this incline wearing full kit and carrying rifles! KJ

Additional material on three visits to the Portreath area as recorded by Michael Bussell.

Please Click here - Additional material provided by Michael Bussell 1965. 1968, and 1996.

Please Click here - Additional material provided by Michael Bussell 1965. 1968, and 1996.

============+++++++++++++++++++=============

============+++++++++++++++++++=============

============+++++++++++++++++++=============

And now to the

Portreath to Poldice Tramway

Portreath to Poldice Tramway

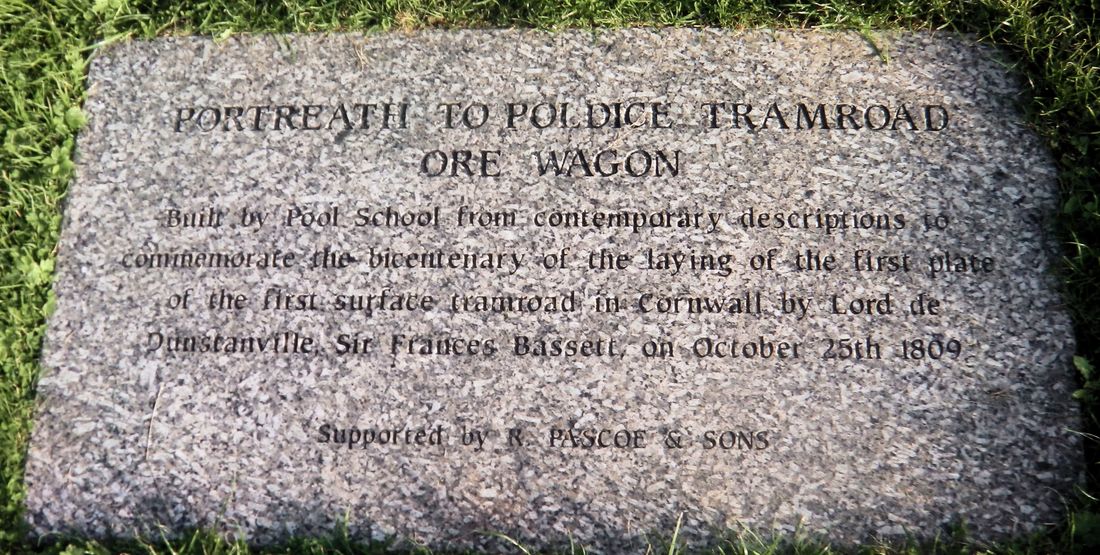

The Portreath Tramroad, or alternatively the Portreath Tramway was opened in 1815, providing a wagonway route from mines near Scorrier in Cornwall, England, to a port at Portreath, from where it could be transported to market by coastal shipping. It was later extended to serve the Poldice mine near St Day and became known as the Poldice Tramroad, or Poldice Tramway.

It was a horse-drawn plateway, and was the first railway in the county of Cornwall, starting operation in 1809.

As a technological pioneer, it soon became technically obsolescent, but continued in use until about 1865. Much of the route can be discerned today and parts of it can be walked or cycled.

See Wikipedia for further details https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portreath_Tramroad

It was a horse-drawn plateway, and was the first railway in the county of Cornwall, starting operation in 1809.

As a technological pioneer, it soon became technically obsolescent, but continued in use until about 1865. Much of the route can be discerned today and parts of it can be walked or cycled.

See Wikipedia for further details https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portreath_Tramroad

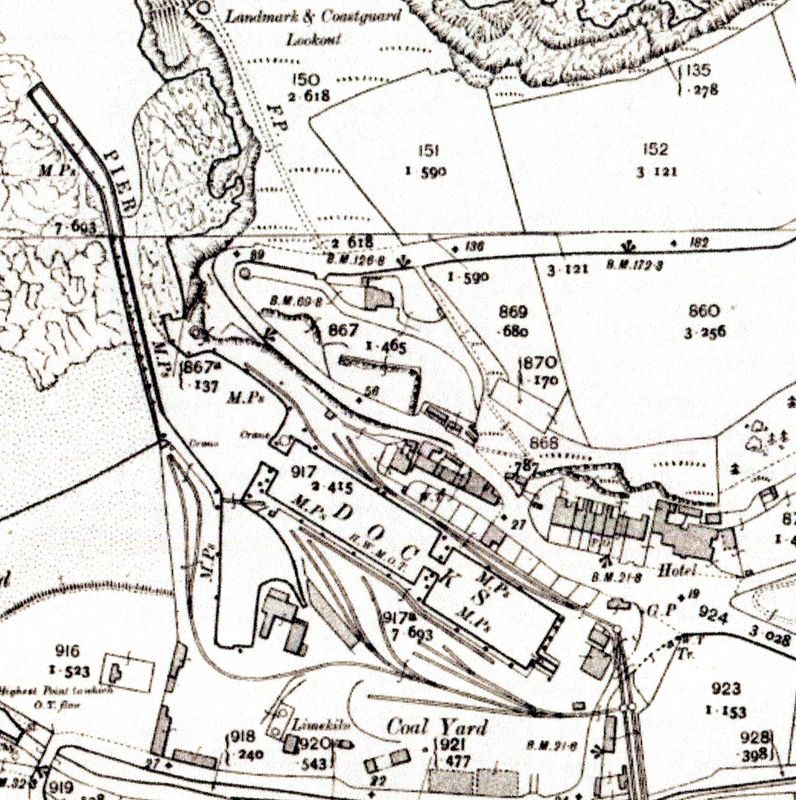

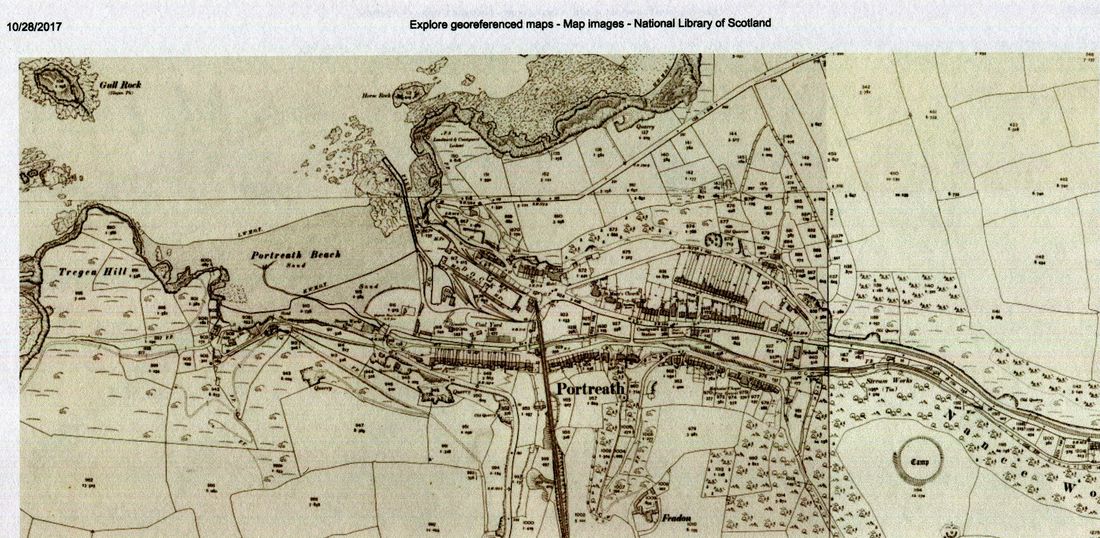

Portreath 1902 1905 Reproduced from a 25 inch map with permission from the National Library of Scotland. This map shows quite clearly how the Poldice Tramway approached the harbour. Coming down the valley close by but about 20' higher than the road the tramway leaving the restrictions of the narrow valley turned sharp right swinging to the NE before making a steady left hand bend before heading directly towards the harbour along a route which later became Sunnyvale Road.

The tramway continues along the north side of a valley and is shortly joined by a metalled road which forms the route to Porthtowan. Although this road is laid along the tramway the bends in the former tramway are too sharp for a modern road and as can be seen here the tramway course is off to the left - it rejoins the modern road after the bend. 3rd June 2010. Copyright Roger Winnen.

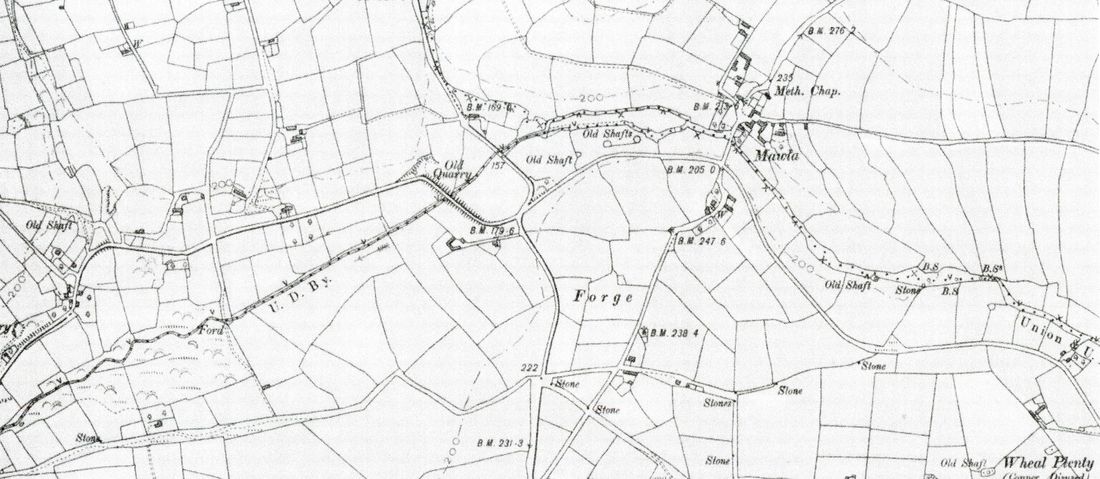

On this map - reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland the tramway can be seen as a road originating from the Portreath direction, left . It can them be followed across to the right passing the Hamlet of Mawla to exit at bottom right heading for Wheal Rose. In the cenre of the map close to the legend 'Old Quarry' the tramway can be seen crossing the valley on an embankment. It is probable that his quarry provided stone for the walls either side of the tram track and possibly for the bridge over a small stream which passes down the valley at this point.

At Wheal Rose, the name of a small hamlet the tramway encounters 'Rodda's Creamery' - the works of which lie across the tramway the route of which as been completely obliterated. However an enterprising individual has established a collection of railwayana which has nothing to do with the tramway but nevertheless makes an interesting feature.

Beyond Rodda's the route of the tramway can be picked up once more where it threads its way through a caravan sales outlet to pass under the Great Western Main line at the site of Scorrier station.

Although we are, for the purpose of this website covering the tramway from Portreath to Poldice on the occasion of this CRS walk we traced the route from Poldice though to the Scorrier area. The party heads through the skew arch of the bridge erected in 1852 to carry the West Cornwall Railway, now the GW, over the tramway. The lighter steel bridge alongside the brick arch carried the platform of Scorrier station. 18th April 2015. Copyright Roger Winnen.

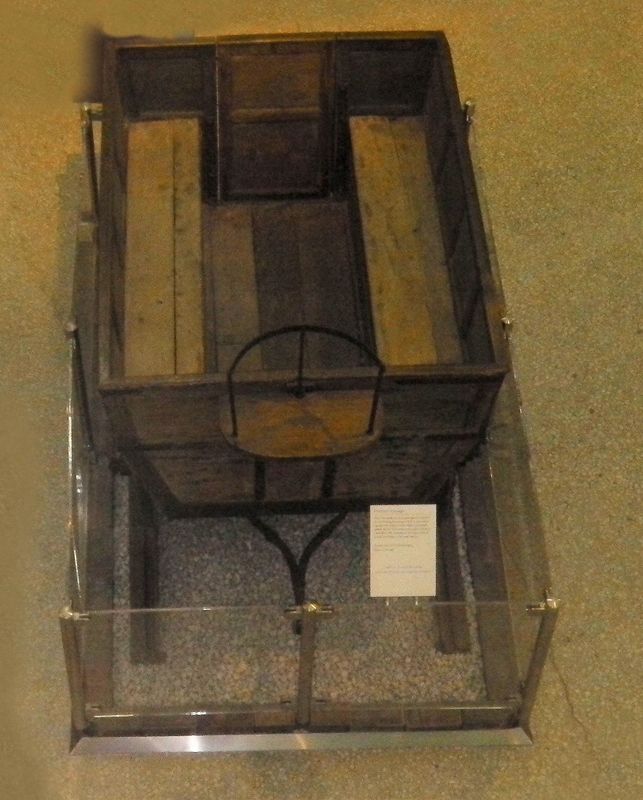

A wagon, fitted with seats and known as the directors wagon long outlived the plateway and was housed in this s building at the rear of the Fox & Hounds at Scorrier. It was subsequently moved to the Holmans Museum and Camborne and then from there to Truro Museum where it now resides. 18th April 2015 Copyright Roger Winnen See the tale of the Poldice Tramway below.

A TALE OF THE POLDICE TRAMWAY Roy Hart

In the 1950s my late father (Leonard Hart) was curator of the Holman Museum at Camborne. The museum was the brainchild of the late Treve Holman, Managing Director of Holman Bros.

Treve Holman devised the plan to buy and re-erect the Cornish beam winding engine from Rostowrack china clay works and re-erect it running under compressed air, at Camborne. Holman’s plan was to have the beam and wheel exposed over the outside street, but the Council vetoed it, fearing road crashes from distracted drivers! Dad and the team rebuilt the engine though, but inside, in 1953.

In about 1957, a wagon (sometimes called the ‘directors’ wagon, because it had seats) from the Poldice to Portreath tramway was discovered in a barn at Scorrier and Treve Holman gave it a home in the Holman Museum. It had to be mounted on track, so Dad and a colleague (and me) were dispatched in a Holman van with picks and shovels to Mawla, to dig up sufficient granite setts to make a stretch of genuine tramway in the original style. There is no closing date for the Poldice to Portreath tramway, but we know from newspapers and other sources that it was abandoned and unused by about 1866. The granite setts on which the ‘plates’ were laid are still visible in many places today.

Holmans’ foundry made the appropriate ‘L’ shaped rails (‘plate’, I suppose, is the proper term = platelayers) and the wagon stood resplendent in the museum until it closed in the 1970s. The wagon (and ‘our’ track) now reposes at Truro museum.

The Holman museum was a sad loss: the Rostowrack engine seems to have been lost, too.

Roy Hart October 2017

In the 1950s my late father (Leonard Hart) was curator of the Holman Museum at Camborne. The museum was the brainchild of the late Treve Holman, Managing Director of Holman Bros.

Treve Holman devised the plan to buy and re-erect the Cornish beam winding engine from Rostowrack china clay works and re-erect it running under compressed air, at Camborne. Holman’s plan was to have the beam and wheel exposed over the outside street, but the Council vetoed it, fearing road crashes from distracted drivers! Dad and the team rebuilt the engine though, but inside, in 1953.

In about 1957, a wagon (sometimes called the ‘directors’ wagon, because it had seats) from the Poldice to Portreath tramway was discovered in a barn at Scorrier and Treve Holman gave it a home in the Holman Museum. It had to be mounted on track, so Dad and a colleague (and me) were dispatched in a Holman van with picks and shovels to Mawla, to dig up sufficient granite setts to make a stretch of genuine tramway in the original style. There is no closing date for the Poldice to Portreath tramway, but we know from newspapers and other sources that it was abandoned and unused by about 1866. The granite setts on which the ‘plates’ were laid are still visible in many places today.

Holmans’ foundry made the appropriate ‘L’ shaped rails (‘plate’, I suppose, is the proper term = platelayers) and the wagon stood resplendent in the museum until it closed in the 1970s. The wagon (and ‘our’ track) now reposes at Truro museum.

The Holman museum was a sad loss: the Rostowrack engine seems to have been lost, too.

Roy Hart October 2017

The directors wagon - fitted with seats is now on display in the Royal Cornwall Museum. The driver sat on the elevated seat at the front. How it was turned at the terminus is a bit of mystery, presumably just manhandled one presumes! One notes that there is no evidence of the granite setts and iron rails on which it stood while at Holmans Museum at Camborne.

Beyond the Fox and Hounds the tramway crosses the main Redruth, Chacewater, Truro road and then accompanies the B3298 road for about half a mile during which time it descends crossing and recrossing the road three times - the final crossing being at Zimapan. From here the route climbs passing Unity Wood towards Little Beside and the terminus at Crofthandy.

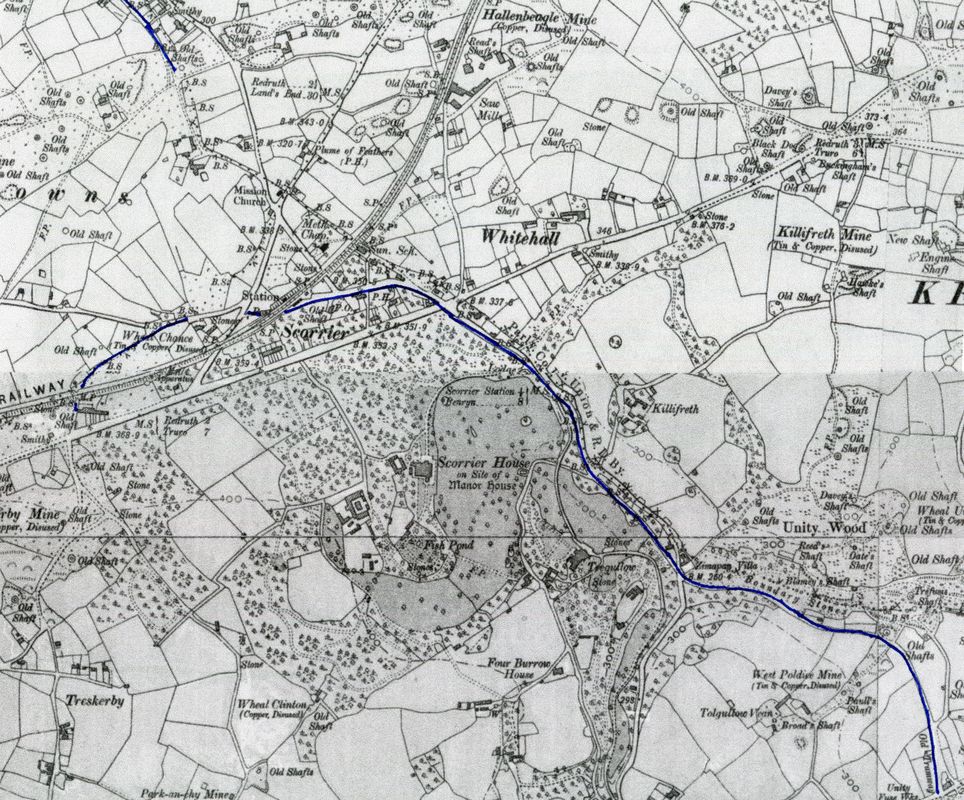

The Poldice tramway, shown as a blue line. came up from Portreath passing around the back (west) side of the hamlet of Wheal Rose.

Past here its route is lost due the Creamery Building. It can be picked up again where it passed beneath the main line and headed off past the back of the Fox and Hounds - the tramway continued on towards the terminus at Crofthandy, however - it is last seen on this map at Little Beside. A branch of the tramway headed off due west passing Wheal Chance and terminating by the main line.

The tramway at 'Little Beside' with obvious pointwork in the foreground. The tramway heads off left towards Zimapan. Unity Wood will be to the right of the tramway which follows the shallow valley towards Zimapan. The tall and very elegant chimney in the background is that of Killifreth mine. This view dated 1972 is by Roger Winnen. Copyright.

On the 18th April the Cornwall Railway Society were treated to a guided walk over the upper section of the Poldice to Portreath tramway. Eric Rabjohns was our very able guide. Some members came fromTruro, their bus is seen arriving, the other half of the party came from Redruth, also on a number 47 bus. Copyright Roger Winnen.